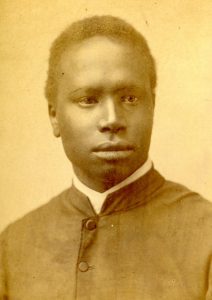

Daniel Sorur Farim Den[g] (c.1859 to 1900), Mr Terence Walz

The First Dinka-born Sudanese Priest

The First Dinka-born Sudanese Priest

Daniel Sorur, a former slave who converted to Christianity, became the first Dinka to be ordained a Catholic priest. He was destined for a brilliant career in the Catholic missionary movement in Africa at the end of the nineteenth century. The great hope of his Comboni missionary mentors was that he would be the agent for the evangelization of his people and other black Africans. Unfortunately, poor health undermined and curtailed his activities, eventually cutting short his life before he could fulfill his promise.

Growing up in Wen de Meren, South Sudan

Daniel Sorur was born Farim Den[g] in 1859 or 1860 in a homestead he called Wen de Meren in the Bahr al-Ghazal province of the Egyptian Sudan (now the country of South Sudan). He was a member of the Jur, one of the Dinka groups then occupying the western bank of the White Nile and the southern side of the Bahr al-Arab River that borders on southern Kordofan province. [1]

Farim’s name means “the saved one” and it was given to him because he was born on a day when the “Arabs” attacked the Dinka. [2]

His father Piok Den[g] died in a hunting accident in 1868 when Farim was perhaps eight or nine, and following the Dinka custom of levirate marriage, his mother Aquid married Piok’s older brother, Akhol. [3] Farim’s older (and only) half-brother Kog died a year later (1869), making him the nuclear family’s sole surviving son. He had three sisters and a foster sister, the daughter of a poor woman who had been taken in by the Den[g] family some years earlier and had been adopted when her mother died.

Farim’s family were chiefly pastoralists who raised cattle and sheep and moved regularly with other clan members across the Bahr al-Ghazal border with southern Kordofan, planting crops when there was time to harvest them. Their farming and grazing patterns inevitably brought them into conflict with the Shilluk, the Nuer, and the Baqqara, resulting in regular loss of lives and livestock. Later, as the Turco-Egyptian government moved into southern Sudan, the Dinka became subject to raids by the Egyptian army and jallaba, petty traders from the northern Sudan who operated on their own or as agents of the government in quest of slaves and other booty. From the 1840s onward, the sale of slaves found a steady market in El Obeid, the capital of Kordofan province, in Khartoum, Upper Egypt, Cairo, and Jidda, particularly male and female children and young women who were wanted for domestic labor and also as slave-wives. The jallaba and the Baqqara eventually worked hand in hand, proving a constant menace to the Dinka. In response the Dinka developed a variety of tactics to defend themselves against these groups, just as they had done to defend themselves against their traditional enemies, the Shilluk.

Despite losing his father when he was eight and his elder brother when he was nine, and despite periodic illnesses, occasional cattle-thieving, and the constant need to seek fresh pastureland for the herds, Farim considered the early years of his life uneventful. In an unpublished manuscript he wrote about his people, “Qual e il mio paese nativo,” which includes valuable autobiographical information, he recounts several early adventures leading to his gradual understanding of the world. One recounts a journey with a cohort of Dinka herders to the farther reaches of the Bahr al-Ghazal River where they encountered the Baggara. He was startled to realize that not all people were as black as the Dinka were. They bartered spears, grain, and sheep for metals and metal-based goods. [4] On another occasion, Farim remembered how the Nile rose unexpectedly high, with the result that their home was flooded. This was not considered a disaster however, since his family escaped harm but it also drew attention to the vagaries of Dinka life on the great river. When he was older, he was sent to work with a related clan that needed young men to look after the cattle. This was a rare opportunity to be among young men of his age group for a number of months. In his discussion of “marriage” in this same manuscript (which was omitted from the official autobiographical work, Memorie, that the missionaries published—see below), it seems that Farim had been promised to a young woman by his mother and step-father and wore a ring in his ear as a sign of his engagement. [5] Of these early memories and of his recollection of Dinka religion and customs in general, the twentieth-century activist priest Marc Nikkel considered Farim’s account sketchy and at times erroneous, and laid part of the blame on the fact that his life with his people ended when he was so young. [6] However, the “Qual e mio paese nativo” manuscript was first worked on in 1883, when Farim was twenty-three or twenty-four, and it is clear from letters he wrote at this time that he was keen to discuss Dinka language and customs with the few European authorities who knew of his people, and we can assume that he retained an active memory of his people and early years. [7]

Enslaved

Farim was captured by Baqqara in 1871, when he was eleven or twelve. Thus began a brutal new chapter in his life, resulting in a journey he could never have imagined as a young boy. What he relates of his capture is typical of the slave narratives that the Comboni missionaries collected and published in their house organs, the Annali dall’Associazione del Buon Pastore and its successor La Nigrizia, [8] but the particular details are nonetheless deeply moving.

The family’s house was located not far from the river, and herdsmen and tillers used to cross it in order to tend the land on the opposite bank. They were also not far from the dry grasslands that Farim calls “desert” in the Memorie, and in times of emergency, men and women and their children used to flee into it in order to escape slave raiders. In the months leading up to their enslavement, the Dinka had escaped or fought off several marauding groups.

The day of his capture, the men folk of Farim’s family were away tending the herd and the women planting a crop when they were surprised by Baqqara and jallaba on horseback and quickly surrounded. Fearing enslavement and being separated from her children, Aquid, whom Farim portrays as a strong and fierce woman, gathered the girls around her and put up a struggle. However, she was wounded by her attacker and all of them were soon captured. In a panic, Farim ran into the grasslands and climbed up a tree to hide. However, the tree was already sheltering another Dinka boy, and both were spotted by the Baqqara horseman who was pursuing the fugitives. They were brought back to the slave encampment where Farim and his mother caught sight of each other. Though hoping to stay together, Aquid and her daughters wound up with different masters, and eventually were separated, never to be seen again. Aquid knew the slavers didn’t like keeping mother and children together, but she persuaded her slaver to trade one of his young captives to Farim’s slaver in exchange for her son—without letting him know they were related—so that at least the two of them could face the bleak future of enslavement together. [9]

After an arduous trip from the Bahr al-Ghazal region, during which additional Dinka clans (the Twic, among them) were attacked and enslaved, Farim and Aquid arrived in El Obeid, the capital of Kordofan. They were left in the compound of Assemani (Uthman), an agent for the principal slaver who was named Abdallahi. Assemani treated him and his mother relatively well. [10] It was Assemani who gave him a new name, “Surur” (Sorur), which means happiness. It was a common name given to slaves at the time.

Farim remained enslaved for two years. He served his master in a variety of capacities—shepherd, doorman, shopkeeper, tailor,—and was often entrusted with special duties. Assemani and Abdallahi decided to return to the South Sudan on a new slaving expedition, and Aquid volunteered to go as the cook on the chance she might find her daughters and bring them back. Assemani didn’t agree with this idea, and so both she and Farim remained in the camp. However, shortly before Assemani and Abdallahi were due to return, Farim or Sorur (as he was now called), was accused of a minor crime and threatened with a harsh punishment. He feared for his life and decided to escape, either into the grasslands to die or to the newly established Comboni mission house in El Obeid where he understood that slaves were given refuge. (He also feared he might be eaten, as this was rumored about whites among Sudanese slaves.) He opted to take his chances with the missionaries. He was welcomed into the house by Mons. Daniel Comboni, who was then in El Obeid and later repeatedly protected Farim against his former owner. In a dramatic scene, Assemani brought Aquid to the mission in an effort to persuade him to return to servitude. Farim refused, and Aquid angrily turned her back on him, saying in harsh terms that she would never see him again. Later Farim heard that she had tried to escape, had been caught, and then punished by being sent to work under harsh conditions in the fields outside Assemani’s encampment. Indeed, he never saw her again and no doubt their last scene together could never be forgotten. These events occurred in late 1873 and represented in dramatic terms the break between his traditional life and his new identity as a modern man and a Christian.

At Mission House in El Obeid, Khartoum and then Europe

In his published autobiography, Farim or Sorur relates how he started learning Italian and Arabic at the Catholic mission in El Obeid, and also began catechism classes. He was baptized by Mons. Comboni in 1874. Comboni had become his mentor and had given him his name; henceforth he was known as Daniel[e] Sorur. He studied for a further year at the Khartoum Mission School, and then was selected in 1876, along with Arturo Morzal [Mursal], an ex-slave from Dar Fur, to be sent to Verona for further studies. Comboni petitioned Pope Pius IX asking that both be admitted to the Collegium Urbanum, Rome, and his request was granted; both boys entered the college in 1877. Sorur studied philosophy and religion in a course of studies that would lead ultimately to the priesthood; Arturo dropped out, opting instead to study medicine.

While he was still in Rome, Sorur began to work on a manuscript about the Dinka and their customs, and one of his several unpublished manuscripts, “Qual il mio paese nativo” (What is my Native Country), was written at this time (ca 1881). Part of this work was included in his autobiography, later serialized in La Nigrizia in 1887-88, and part was translated into German and published in 1888 and then republished in 1890 and 1900. [11] It was also during the period in Rome that he began another work called “Le pene dei negri schiavi in Africa” (The Travails of Black Slaves in Africa) in which he developed his ideas about the salvation of black people through the instrument of Christianity. In it he also equates Islam with modern slavery and the strangulation of the African spirit, and opines that his black brethren will never progress unless they escape Islam and embrace Christianity. The editing of his work was finished around 1885. [12] By the end of his formal studies, Sorur had not only shown considerable intellectual capacities, but was also fluent in Italian, French, German and English. He had established himself as a spokesman for the conversion of Africans to Christianity, a role for him that the Comboni mission fathers must fervently have sought.

In 1883, however, Sorur fell seriously ill [13] and was sent to recuperate in the warm and dry climate of Cairo, where the Comboni mission had constructed a new church and two mission schools in the new and fashionable quarter of the city known as Ismailia. After seven months there, he was deemed well enough to finish his studies at the Jesuit University in Beirut, which he did in 1886. In the summer he went to Ghazir, a village in the Lebanese mountains, to undertake further studies in Arabic and to teach French and Italian.

Return to Egypt and a Short Sojourn in Sudan

Later in 1886, he returned to Cairo, where he was ordained the following spring by Bishop Francesco Sogaro in a ceremony at the Sacred Heart Church in downtown Cairo. According to his autobiography, his ordination caused jubilation among the city’s Catholics and Sudanese, being the first “black” to become a priest. [14] This was the time when Cairo’s ex-slave and trans-Saharan African populations were perhaps at their height. Also, it was a time when many other Sudanese had sought refuge there from the newly installed Mahdist government in Omdurman. [15]

After his ordination, Sorur’s memoir (Memorie) was serialized in five issues of the mission bulletin La Nigrizia. Its purpose was clearly to introduce him to a wider audience, including the European financial supporters of the Comboni mission in Africa. It contains dark references to struggles between the Dinka, the Shilluk, the Baggara, and the slavers, be they itinerant merchants from the north (jallaba) or Turco-Egyptian government officials, but also the narrative of his dramatic escape from slavery, his mother’s doom-laden rejection, and his decision to embrace a life with the Christians over a life under Islamic rule. This latter part was the message that the missionaries wished to impart to the thousands of non-Muslim Sudanese who had been forced into slavery in the nineteenth century, and to the mission’s backers who supported the crusade against slavery and their efforts to Christianize Africa.

With his studies now completed, Sorur was kept busy in Cairo teaching Arabic to Sudanese and other Africans while the Comboni Fathers decided what to do with him next. [16] Trained as an evangelical priest, they wanted him to begin work in the Sudan. However, at this time only Sawakin and the eastern Red Sea coast remained free of Mahdist control. In late 1887 he was posted there and put in charge of its mission school. Although his stay was short, it was a highly eventful time. The port city was besieged by Mahdist forces, and the siege was not lifted until the end of 1888. Sorur’s role during the siege was later praised in the mission literature. In a letter to Bishop Sogaro in Cairo, Sorur reports on the Battle of Sawakin on December 20, 1887 in which Sudanese battalions fought off an attack by Uthman Digna, and how as a consequence he was unable to send in his monthly account since he had not yet paid the grocer, the baker, or the butcher. [17] His normal duties during the year involved teaching catechism and Arabic to young Christian adepts (probably ex-slaves), and greeting people traveling down the Red Sea. During this time he met two American priests from South Bend, Indiana, and later corresponded with Father Daniel Hudson of Notre Dame. In an extant letter to him, he recalled that it was “twenty years” since his conversion to Christianity (actually it was only fourteen) and that he regretted the fact that his mother and sisters remained “Muslim.” [18]

Fund-Raising Sojourn in Europe

Sorur spent only eighteen months in Sudan. The mission in Verona seems to have realized his value as the spokesman for the Combonis’ work in Africa and they brought him back to Europe in 1889 to participate in a major fund-raising trip for the mission being undertaken by Bishop Franz Xavier Geyer. The aim of the journey was to raise money for the Central African Mission’s institutions in Cairo (which by now had expanded to new grounds located on the island of Zamalek) and for the construction of churches in Sawakin and Helwan. Fluent in French as well as in Italian, German, and English, Sorur enjoyed great success as a speaker and proved especially popular in Austria and Germany. His ability in languages and his gentle demeanor won him many friends. Many Europeans had never seen a black person before, and were often stunned by his appearance. [19] Later Sorur joined for a short period Cardinal Lavigerie’s ardent crusade in Europe against slavery in Muslim northern Africa.

Sorur must often have lectured on slavery in Africa. In addition to his work Le Pene dei negri schiavi in Africa, he found time to write a longer manuscript called Lo stato reale dei Negri (The Real Condition of the Blacks). It is a serious effort to discuss the religious and social ideas of Africans in various parts of the world in which they lived. It was turned over to be translated into German and to be published but in fact it never was. [20]

Return to Cairo and Final Years

Ill-health was probably the reason for his return to Cairo in 1891, where Sorur remained during the final period of his life, teaching at the mission schools in Cairo and later Helwan, where most of his students were Egyptians or sons of Europeans. Helwan had become famous as a spa, and no doubt the baths and the dry climate helped Sorur cope with his illness. Biographies written about him do not suggest that he was involved in the education in Zamalek of ex-slaves or other Sudanese in Cairo at the end of the nineteenth century where the Comboni Institute taught useful trades and catechism. Rather, the surviving photographs of him at their boys’ school in Helwan picture him with young Egyptian students. Sudan remained closed off until it was reconquered by an Anglo-Egyptian force in 1898. But by that time, his health was failing him.

Sorur died in Cairo at the Abbasiyya Hospital on January 11, 1900. [21] He is believed to be buried in the common grave of the Comboni brothers and sisters in Helwan, but in fact his name is not mentioned in the plaque in the mausoleum. A brilliant career as an evangelical among his people eluded him. After he died, the Comboni missionaries were able to return to the Sudan, and in 1930, his autobiography was translated into English, [22] though never published. Clearly the missionaries believed the truncated career of this unusual man deserved to resonate with their new converts. [23]

Notes

- On the Dinka, a modern term, Stephanie Beswick, Sudan’s Blood Memory (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2004), 13-14.

- This story, perhaps apocryphal, is included in the unpublished manuscript by Anon, “Slave & Priest,” in the Archivio comboniani Roma, A/30/1/1, 2 and 19; included in Aldo Benetti, Don Daniele Sorur, Salvare l’Africa con l’Africa (Helwan, Egypt, privately printed, 1996), 85-120.

- For the main biographical facts, Daniel Sorur, “Memorie scritte dal R.P. Daniele Sorur Pharim Den,” La Nigrizia 5 (1887), 146-51, 171-77; 6 (1888): 56-59, 77-84, 111-119.

- Qual e il mio paese, Archivio comboniani Roma, A/30/2/9/, 10.

- Qual e il mio paese, 22-23.

- Marc Nikkel, “Daniel Sorur Farim Deng: ‘Comboni’s Adoptive Son’,” in Andrew C. Wheeler and William B. Anderson, eds, Announcing the Light: Sudanese Witnesses to the Gospel (Nairobi: Paulines, 1998), 44. In another section, Nikkel calls the work “stilted, void of subjectivity or commitment.”

- I am grateful to Fr. Joaquim Valente da Cruz, president of the Studium Combonianum, for guiding me through the dating of thes manuscripts in the Comboni archives; for the text of the extant letters from him dated 1883, when he was recovering from ill health, it is clear he had read the works by Fr. Joseph Lanz and Fr. Mitterrutzner published in the 1860s. I am also indebted to Fr. Joaquim for sharing these letters with me.

- http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nigrizia; for example, see Maria Liscok. For other slave narratives, see the story of St. Bakhita Josephine, also known as Josephine Bakhita, “A Universal Sister: Blessed Bakhita Josphine,” in Wheeler, Announcing the Light, 23-28.

- Following Memorie, part 3: 175-76.

- Sorur says he was “treated as a son”: Memorie, part 4:80

- Other pieces were excerpted by E. V. Toniolo, “An Early Manuscript on the Dinka Written by a Member of this Tribe,” Sudan Notes and Records 41 (1960), 107-13; later published Elias Toniolo and Richard Hill, “A Dinka Priest Writing on his own People,” The Opening of the Nile Basin, 196-203 (London: C. Hurst and Company, 1974), 196-203.

- Fr. Joaquim, email to the author March 29, 2011. It was published in Italian in 1964 by Renato Boccassino (Roma: Euntes Docete). See also Nikkel, 44, who found Sorur’s views “passionate.”

- Letters from the period mentioning “coughing up blood,” suggesting tuberculosis. Giulianelli to Simeoni, Cairo, 11 luglio 1883, Archivio Comboniani Roma, A/30/13/3 (minuta).

- Deng says they “were half mad of joy”: Nigrizia 5 (1887), 123.

- According to the 1882 census, the Sudanese and Nubian population in Cairo numbered 15,428; after the Mahdist revolt in 1882, several thousand Sudanese must have come to the capital. The census figures are found in Egypt, Direction du recensement, Recensement général de l’Égypte, 2 v. in 3, Cairo, Imprimerie nationale de Boulaq, 1884-85.

- Casimiro Giacomelli, Il Mio Giornale, mss in Archivio Comboniani Roma, A 145/8, 2 vols., vol. 1, 156, photocopy viewed at Comboni House, Cairo.

- Sorur to Sogaro, Sawakin, 27 Dicembre 1888, Archivio Comboniani Roma, A/30/13/36. On his time in Sawakin, Introduction (translated into Italian) to the Polish edition of Sorur’s “Memorie,” Pamietnek Niewolnika Afrykanskiego, Krakow, 1891.

- University of Notre Dame Archives, C/WKC CHUD, Den to Hudson, l January 11, 1889. On the stay in Sawakin, see also Fr. E. V. Toniolo, “An Early Manuscript on the Dinka Written by a Member of this Tribe,” Sudan Notes and Records 41 (1960), 107.

- ACR A/30/1/1, “Slave & Priest,” 1. The copy I used was a photocopy reproduced in Benetti, Don Daniele Sorur, 85-120.

- It is now in the Archivio Comboniani Roma, A/30/2/10. The background on the history of this manuscript was provided in an email from Fr. Joaquim, April 20, 2011.

- See his obituary by Giuseppe Beduschi, “Il Rev. P. Daniele Sorur, nero della tribu dei Denka, missionario dell-Africa Centrale,” Nigrizia 18 (1900), 27-29, 44-45, 74-75.

- Slave & Priest.

- An assessment of Deng and his career can be found in Fulvio De Giorgi, “Tra Africa e Europa: Daniele Sorur Pharim Den,” Contemporanea, Rivista di storia dell ‘800 e del ‘900, 7, 1 (January 2004), 39-67; reprinted in Archivio Comboniano 42, 1 (2004).

Sorur bibliography

Archivio comboniani Roma (ACR)

Anon, “Daniele Den Farin Sorur, Alunno del Collegio Urbano primo fiore del Sacerdozio indigeno nell’Africa Centrale” Alma Mater, Rome, Nos. 9-10 (1930), 87-94.

Anon, “Slave & Priest,” ms in ACR, A/30/1//1; included in Benetti, Don Daniele Sorur, Salvare l’Africa con l’Africa, 85-120.

Giulianelli to Simeoni, Cairo, 11 luglio 1883, Archivio Comboniani Roma, A/30/13/3 (minuta)

Beduschi, Giuseppe. 1900. “Il Rev. P. Daniele Sorur, nero della tribu dei Denka, missionario dell-Africa Centrale,” Nigrizia 18, 27-29, 44-45, 74-75.

Benetti, Aldo, Don Daniele Sorur, “Salvare l’Africa con l’Africa,” Helwan: privately printed, 1996.

Beswick, Stephanie. 2004. Sudan’s Blood Memory. Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

Debrunner, Hans Werner, Presence and Prestige: Africans in Europe: A History of Africans in Europe before 1918, Basel: Basler Afrika Biblographien, 1979, 328-330.

Di Falco, Rossana di Falco, Un Missionario africano di Europe: Il caso di Padre D. Sorur, Dissertation, Aquila, 1998.

De Giorgi, Fulvio. 2004. “Tra Africa e Europa: Daniele Sorur Pharim Den,” Contemporanea, Rivista di storia dell ‘800 e del ‘900, 7, 1, 39-67; reprinted in Archivio Comboniano 42, 1 (2004).

Egypt, Direction du recensement, 1884-85. Recensement général de l’Égypte, 2 v. in 3, Cairo, Imprimerie nationale de Boulaq.

Giacomelli, Casimiro. Il Mio Giornale, 2 vols., ms in ACR, A 145/8. Photocopy viewed at Comboni House, Cairo.

Nikkel, Marc. 1998. “Daniel Sorur Farim Deng: ‘Comboni’s Adoptive Son’,” in Andrew C. Wheeler and William B. Anderson, eds., Announcing the Light: Sudanese Witnesses to the Gospel. Nairobi: Paulines.

Powell, Eve M. Troutt. 2012. Tell This in my Memory: Stories of Enslavement from Egypt, Sudan and the Ottoman Empire. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. Chap. 5 contains a biographical treatment of Sorur (171-85).

Santandrea, Stefano. 1948. “Bibliografia di studi africani della Missione dell’Africa central.” Verona: Missioni Africane, 30, 31-32, 48.

Sorur, Daniele. “Diary of an African Slave, Introduction” (translated into Italian) to the Polish edition of his “Memorie.” Pamietnek Niewolnika Afrykanskiego, Krakow, 1891.

_____. Letters. In ACR, A/30/13.

_____. 1887-88. “Memorie scritte dal R.P. Daniele Sorur Pharim Den,” serialized in La Nigrizia 5 (1887), 146-51, 171-77; 6 (1888): 56-59, 77-84, 111-119.

_____. 1964. Le pene dei negri schiavi in Africa: manoscritto conservato nell’Archivio delle Missioni africane di Verona, edito con un’introduzione e note da Renato Boccassino. Roma: Euntes Docete.

_____. Qual e il mio paese. Ms in ACR, A/30/2/9

_____. Den[g] to Hudson, l January 11, 1889, in the University of Notre Dame Library, Archives, C/WKC CHUD.

- V. Toniolo, E. V. 1960. “An Early Manuscript on the Dinka Written by a Member of this Tribe,” Sudan Notes and Records 41, 107-13; later published in Elias Toniolo and Richard Hill, “A Dinka Priest Writing on his own People,” The Opening of the Nile Basin (London: C. Hurst and Company, 1974), 196-203.

This biography was researched and written by Dr. Terence Walz, Independent Scholar based in Washington D.C., co-editor with Kenneth M. Cuno of Race and Slavery in the Middle East: Histories of Trans-Saharan Africans in Nineteenth-Century Egype, Sudan, and the Ottoman Mediterranean (American University in Cairo Press, 2010).